A Guide to Venice's "Shark Tooth Capital of the World"

Hunting for fossilized shark teeth is a treasured Sarasota County pastime, and the best place to find them is along the coastline of Venice, Florida.

It's a picture-perfect morning on Southwest Florida's Venice beach, as the cloudless royal blue sky meets the far-off horizon. The emerald-green Gulf of Mexico gently laps onto the sandy shoreline, and a few barefooted beachcombers are off in the distance, searching for the discarded teeth of the ocean’s infamous hunters. As the "Shark Tooth Capital of the World," nature lovers and marine biology enthusiasts alike come from near and far to see if they can get their hands on the elusive fossilized teeth of Gulf Coast's many shark species. Luckily, there are plenty of teeth to go around, as well as many sharky activities for the whole family to bite into!

Where to Find Shark Teeth

The Gulf beaches in and around Venice, Florida, hold a bountiful cache of fossilized shark teeth. Shark teeth collectors say the best places to look for the fossils are any beach accesses at or around the Venice Jetty – including Venice Beach, Caspersen Beach, Casey Key and Manasota Key.

The Venice Fishing Pier at Brohard Park is right in the heart of shark's tooth country and an ideal place to begin your journey, especially if you are new to the area. Before you start searching the sands, take a walk out on the scenic 740-foot pier and stop at Papa's Bait Shop. There you can rent or buy the “Venice Snow Shovel," the screened basket fitted onto a handle to help you dig shark teeth. And after a day of fossil hunting, you might want to celebrate your bounty at Fins at Sharky's restaurant with a spectacular Gulf view where you can enjoy a well-deserved and delicious fish sandwich with a beverage to toast the sunset.

Venice History & Species Found

Ten million years ago, when Florida was submerged underwater, the area was teeming with sharks. Over time, as the water receded giving way to land, the prehistoric sharks died - their skeletons disintegrated, but their fossilized teeth remained. The Venice coastal area, just south of Sarasota, sits on top of a fossil layer that runs 18-35 feet deep. With storms and waves, the fossils are slowly driven into the shallow waters and then up onto the beach.

There are high chances you will find Sand, Lemon, Mako, Bull, Whitetip and Megalodons – just to name a few of the common species found in the sands of Venice and Caspersen beaches.

Find Sharks' Teeth by Beach or Boat

By Beach: Most people who look for shark teeth simply stroll along the beach scanning the sand for the shiny black teeth. Others, seeking faster results, walk to the water's edge where the waves break and there is a foot-high drop-off ledge. They reach down to the edge of the drop-off or even wade out a few feet into the water to scoop up sand and shells. Some use a shovel, a kitchen strainer or just scoop the sand and shells with their hands. Once scooped, they bring it back to the beach and pour it onto the sand. Then they sit on the beach and sift through, looking for their prizes. Other fossil parts, bits of coral, interesting shells or small pebbles may catch the eye, but it is likely that at least one or more teeth will be found in most large scoops.

By Boat: Most shark teeth are from 1/8" to 3/4" or even a bit larger. However, the really large shark teeth are usually farther out offshore and may require dive equipment to locate. Local Venice dive boats and guides will take you out as they cruise a few miles from the shore. In fact, several boat captains charter trips along the Venice coastline in search of prehistoric fossils and shark teeth. Call any local Venice dive shop and they will recommend captains/guides specializing in fossils to get you suited up and diving for the big boys!

Items You Will Need:

- Hat and sunscreen for protection.

- Small mesh baggie or container for your finds.

- For onshore hunting: a sand flea rake/scooper or Venice “snow" shovel basket, which you can buy at the pier or Ace Hardware (optional). A regular kitchen sifter will also do!

- For offshore hunting, scuba or free diving equipment (optional).

Get a Guidebook After Hunting

Before you know it, you'll have a collection of shark teeth and begin wondering why they are so different in shape, color and size. Some are pointier or fatter, or even sharper at the ends. Some are pearly white while others will be more of a gray-black color. With a handy guidebook found at local bookstores, it will provide pictures that assist you with teeth identification of the individual known shark species.

More Sharky Attractions

If you're in the Sarasota area around April, don't miss the annual Venice Sharks' Tooth Festival! The highly-anticipated, family-fun event shows off magnificent shark teeth display every year, including prehistoric fossil collections, sharks' jaws, stingray spine fragments, stingray teeth, alligator teeth, sea biscuits and more. In addition, there are interactive exhibits, fossil talks, food and art vendors, local bands playing and much more!

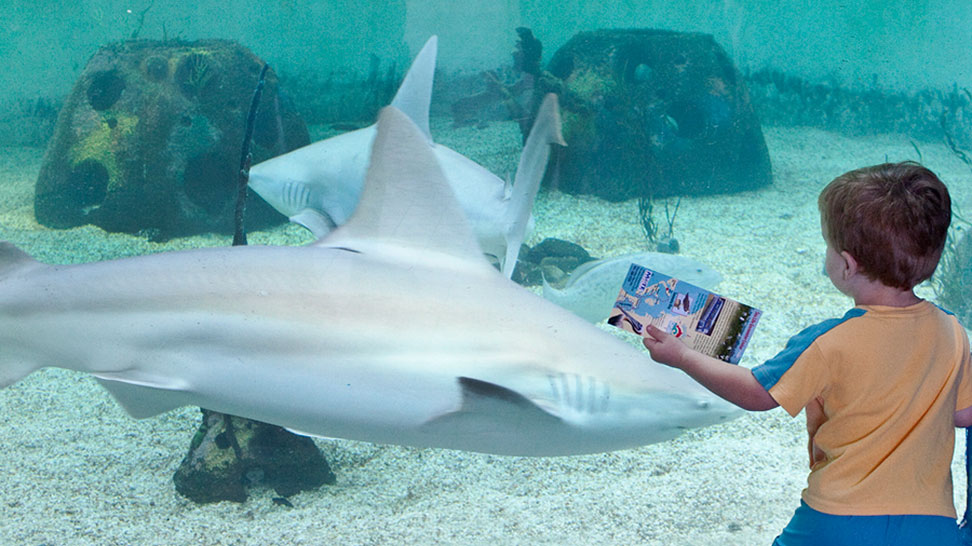

Can't get enough of sharks? Once you’ve found your fill of fossilized teeth, head to Mote SEA to see them live and in action during your visit to Sarasota County! The aquarium’s state-of-the-art exhibit features shark species such as Bonnethead, Sandbar, Nurse, and Blacknose.

You can also take a fun treasure hunt of sorts on a self-guided sculptural Shark Spotting tour throughout Historic Downtown Venice. It features 10 bronze sculptures of native species of living and prehistoric sharks. These works of art were specially created by internationally known fine artists at Sarasota’s Bronzart Foundry. Walk the sharky loop and find all 10 utilizing this brochure and map of clues!

Shark Tooth Facts

- Sharks produce 20,000-25,000 teeth over their lifetime.

- Shark teeth don’t have roots, so they fall out easily while the shark is eating.

- Sharks typically lose at least one tooth per week.

- Shark teeth are arranged in conveyor belt rows and can be replaced within a day.

- Most sharks have five rows of teeth; the bull shark has fifty rows of teeth.

- Baby sharks (pups) are born with a complete set of teeth.

- Shark teeth sizes can range from 1/8" – 3.5"or more.

- 1" of the mighty Megladon's tooth represents 10 feet of the actual length of the prehistoric shark.

![Boat parking at The Crow’s Nest in Venice [Photo: Lauren Jackson]](/sites/default/files/styles/popular_stories_teaser/public/2023-import/The-Crow%2527s-Nest-cropped__OPT.jpg.webp?itok=ycs37M-O)